I’m living in an age

That calls darkness light

[…]

I’m living in an age

Whose name I don’t know

I’m living in an age

That calls darkness light

[…]

I’m living in an age

Whose name I don’t know

Espero participar en el Octavo Simposio de Estudiantes de Filosofía de la PUCP (facebook oficial), habiendo mandado una sumilla que comparto a continuación:

«Soy un hombre enfermo… Soy un hombre malo».

– El hombre del subsuelo, de Fiódor Dostoievski.

«Si bien tu mente funciona, tu corazón está oscurecido por la depravación, y sin un corazón puro no puede existir una conciencia total, recta».

– El oponente imaginario del hombre de subsuelo.

Existe un gran misterio en la ética de Immanuel Kant. Se trata de cómo la razón pura puede ser en sí misma práctica en el ser humano. Esto significa que la ley moral, el mandato que nos obliga categóricamente a respetar el valor absoluto de la libertad en uno mismo y en los demás, sea un mandato que opere efectivamente, de alguna forma, dentro de nosotros. Lo que está en juego es la realidad de la moralidad kantiana, es decir, que no sea una mera quimera o una fantasmagoría… o el sueño de un filósofo visionario. Sobre la base de este gran supuesto es que Kant elabora su visión de una maldad innata en nuestra especie, en el albedrío de cada individuo, en el corazón (Herz), propiamente. La ponencia se centrará, de forma precisa, en examinar qué tipo de discurso es posible acerca del mal moral, abordando, primero, el rol que juega la figura del corazón en los escritos estrictamente morales de Kant, como el lugar donde la ley moral entra en contacto con la sensibilidad del ser humano, ejerciendo su influencia decisiva, lugar también donde se dan nuestros más profundos razonamientos éticos, que permanecen siempre en última instancia insondables; en segundo lugar, se profundizará en la figura del corazón tal como es abordada en La Religión dentro de los límites de la mera Razón, como aquel momento de espontaneidad inescrutable del albedrío, concluyendo que el mal radical no sólo es parte de un discurso religioso e indemostrable, si bien racional, sino que toda la ética de Kant está atravesada por un elemento propiamente religioso, a saber, el misterio que supone la existencia de un imperativo categórico, idea que deja a la razón impotente al tratar de hacerla inteligible.

Trataré de presentar, de forma concreta y preparada para la oralidad, lo central de mi tesis de Maestría, propiamente.

Comparto mis sumillas de años anteriores: 2009, 2010 y 2011.

Así es, ya con tres años de existencia, abrimos nuestro portal en facebook, que pueden acceder vía esta dirección:

http://www.facebook.com/lossuenosdeunvisionario

Consideramos que dicha página es más que un mero portal para compartir las entradas de este blog, o una repetición de lo que aquí se punlica. Este espacio seguirá, por supuesto, operativo. Más bien, el nuevo medio se presta para compartir, como complemento del trabajo que se viene realizando acá, notas breves, imágenes, citas, artículos interesantes, dejando este espacio como un lugar para textos más elaborados.

Los invitamos, pues, a seguirnos.

What follows is the complete short story which Isaac Asimov considered his own best.

The last question was asked for the first time, half in jest, on May 21, 2061, at a time when humanity first stepped into the light. The question came about as a result of a five-dollar bet over highballs, and it happened this way:

Alexander Adell and Bertram Lupov were two of the faithful attendants of Multivac. As well as any human beings could, they knew what lay behind the cold, clicking, flashing face–miles and miles of face–of that giant computer. They had at least a vague notion of the general plan of relays and circuits that had long since grown past the point where any single human could possibly have a firm grasp of the whole.

Multivac was self-adjusting and self-correcting. It had to be, for nothing human could adjust and correct it quickly enough or even adequately enough. So Adell and Lupov attended the monstrous giant only lightly and superficially, yet as well as any men could. They fed it data, adjusted questions to its needs and translated the answers that were issued. Certainly they, and all others like them, were fully entitled to share in the glory that was Multivac’s.

For decades, Multivac had helped design the ships and plot the trajectories that enabled man to reach the Moon, Mars, and Venus, but past that, Earth’s poor resources could not support the ships. Too much energy was needed for the long trips. Earth exploited its coal and uranium with increasing efficiency, but there was only so much of both.

But slowly Multivac learned enough to answer deeper questions more fundamentally, and on May 14, 2061, what had been theory, became fact.

The energy of the sun was stored, converted, and utilized directly on a planet-wide scale. All Earth turned off its burning coal, its fissioning uranium, and flipped the switch that connected all of it to a small station, one mile in diameter, circling the Earth at half the distance of the Moon. All Earth ran by invisible beams of sunpower.

Seven days had not sufficed to dim the glory of it and Adell and Lupov finally managed to escape from the public function, and to meet in quiet where no one would think of looking for them, in the deserted underground chambers, where portions of the mighty buried body of Multivac showed. Unattended, idling, sorting data with contented lazy clickings, Multivac, too, had earned its vacation and the boys appreciated that. They had no intention, originally, of disturbing it.

They had brought a bottle with them, and their only concern at the moment was to relax in the company of each other and the bottle.

“It’s amazing when you think of it,” said Adell. His broad face had lines of weariness in it, and he stirred his drink slowly with a glass rod, watching the cubes of ice slur clumsily about. “All the energy we can possibly ever use for free. Enough energy, if we wanted to draw on it, to melt all Earth into a big drop of impure liquid iron, and still never miss the energy so used. All the energy we could ever use, forever and forever and forever.”

Lupov cocked his head sideways. He had a trick of doing that when he wanted to be contrary, and he wanted to be contrary now, partly because he had had to carry the ice and glassware. “Not forever,” he said.

“Oh, hell, just about forever. Till the sun runs down, Bert.”

“That’s not forever.”

“All right, then. Billions and billions of years. Twenty billion, maybe. Are you satisfied?”

Lupov put his fingers through his thinning hair as though to reassure himself that some was still left and sipped gently at his own drink. “Twenty billion years isn’t forever.”

“Well, it will last our time, won’t it?”

“So would the coal and uranium.”

“All right, but now we can hook up each individual spaceship to the Solar Station, and it can go to Pluto and back a million times without ever worrying about fuel. You can’t do that on coal and uranium. Ask Multivac, if you don’t believe me.”

“I don’t have to ask Multivac. I know that.”

“Then stop running down what Multivac’s done for us,” said Adell, blazing up. “It did all right.”

“Who says it didn’t? What I say is that a sun won’t last forever. That’s all I’m saying. We’re safe for twenty billion years, but then what?” Lupov pointed a slightly shaky finger at the other. “And don’t say we’ll switch to another sun.”

There was silence for a while. Adell put his glass to his lips only occasionally, and Lupov’s eyes slowly closed. They rested.

Then Lupov’s eyes snapped open. “You’re thinking we’ll switch to another sun when ours is done, aren’t you?”

“I’m not thinking.”

“Sure you are. You’re weak on logic, that’s the trouble with you. You’re like the guy in the story who was caught in a sudden shower and who ran to a grove of trees and got under one. He wasn’t worried, you see, because he figured when one tree got wet through, he would just get under another one.”

“I get it,” said Adell. “Don’t shout. When the sun is done, the other stars will be gone, too.”

“Darn right they will,” muttered Lupov. “It all had a beginning in the original cosmic explosion, whatever that was, and it’ll all have an end when all the stars run down. Some run down faster than others. Hell, the giants won’t last a hundred million years. The sun will last twenty billion years and maybe the dwarfs will last a hundred billion for all the good they are. But just give us a trillion years and everything will be dark. Entropy has to increase to maximum, that’s all.”

“I know all about entropy,” said Adell, standing on his dignity.

“The hell you do.”

“I know as much as you do.”

“Then you know everything’s got to run down someday.”

“AU right. Who says they won’t?”

“You did, you poor sap. You said we had all the energy we needed, forever. You said ‘forever.’ “

It was Adell’s turn to be contrary. “Maybe we can build things up again someday,” he said.

“Never.”

“Why not? Someday.”

“Never.”

“Ask Multivac.”

“You ask Multivac. I dare you. Five dollars says it can’t be done.”

Adell was just drunk enough to try, just sober enough to be able to phrase the necessary symbols and operations into a question which, in words, might have corresponded to this: Will mankind one day without the net expenditure of energy be able to restore the sun to its full youthfulness even after it had died of old age?

Or maybe it could be put more simply like this: How can the net amount of entropy of the universe be massively decreased?

Multivac fell dead and silent. The slow flashing of lights ceased, the distant sounds of clicking relays ended.

Then, just as the frightened technicians felt they could hold their breath no longer, there was a sudden springing to life of the teletype attached to that portion of Multivac. Five words were printed: insufficient data for meaningful answer.

“Not yet,” whispered Lupov. They left hurriedly. By next morning, the two, plagued with throbbing head and cottony mouth, had forgotten the incident.

Jerrodd, Jerrodine, and Jerrodette I and II watched the starry picture in the visiplate change as the passage through hyperspace was completed in its non-time lapse. At once, the even powdering of stars gave way to the predominance of a single bright marble-disk, centered.

“That’s X-23,” said Jerrodd confidently. His thin hands clamped tightly behind his back and the knuckles whitened.

The little Jerrodettes, both girls, had experienced the hyperspace passage for the first time in their lives and were self-conscious over the momentary sensation of inside-outness. They buried their giggles and chased one another wildly about their mother, screaming, “We’ve reached X-23–we’ve reached X-23–we’ve–”

“Quiet, children,” said Jerrodine sharply. “Are you sure, Jerrodd?”

“What is there to be but sure?” asked Jerrodd, glancing up at the bulge of featureless metal just under the ceiling. It ran the length of the room, disappearing through the wall at either end. It was as long as the ship.

Jerrodd scarcely knew a thing about the thick rod of metal except that it was called a Microvac, that one asked it questions if one wished; that if one did not it still had its task of guiding the ship to a preordered destination; of feeding on energies from the various Sub-galactic Power Stations; of computing the equations for the hyperspatial jumps.

Jerrodd and his family had only to wait and live in the comfortable residence quarters of the ship.

Someone had once told Jerrodd that the “ac” at the end of “Microvac” stood for “analog computer” in ancient English, but he was on the edge of forgetting even that.

Jerrodine’s eyes were moist as she watched the visiplate. “I can’t help it. I feel funny about leaving Earth.”

“Why, for Pete’s sake?” demanded Jerrodd. “We had nothing there. We’ll have everything on X-23. You won’t be alone. You won’t be a pioneer. There are over a million people on the planet already. Good Lord, our great-grandchildren will be looking for new worlds because X-23 will be overcrowded.” Then, after a reflective pause, “I tell you, it’s a lucky thing the computers worked out interstellar travel the way the race is growing.”

“I know, I know,” said Jerrodine miserably.

Jerrodette I said promptly, “Our Microvac is the best Microvac in the world.”

“I think so, too,” said Jerrodd, tousling her hair.

It was a nice feeling to have a Microvac of your own and Jerrodd was glad he was part of his generation and no other. In his father’s youth, the only computers had been tremendous machines taking up a hundred square miles of land. There was only one to a planet. Planetary ACs they were called. They had been growing in size steadily for a thousand years and then, all at once, came refinement. In place of transistors had come molecular valves so that even the largest Planetary AC could be put into a space only half the volume of a spaceship.

Jerrodd felt uplifted, as he always did when he thought that his own personal Microvac was many times more complicated than the ancient and primitive Multivac that had first tamed the Sun, and almost as complicated as Earth’s Planetary AC (the largest) that had first solved the problem of hyperspatial travel and had made trips to the stars possible.

“So many stars, so many planets,” sighed Jerrodine, busy with her own thoughts. “I suppose families will be going out to new planets forever, the way we are now.”

“Not forever,” said Jerrodd, with a smile. “It will all stop someday, but not for billions of years. Many billions. Even the stars run down, you know. Entropy must increase.”

“What’s entropy, daddy?” shrilled Jerrodette II.

“Entropy, little sweet, is just a word which means the amount of running-down of the universe. Everything runs down, you know, like your little walkie-talkie robot, remember?”

“Can’t you just put in a new power-unit, like with my robot?”

“The stars are the power-units, dear. Once they’re gone, there are no more power-units.”

Jerrodette I at once set up a howl. “Don’t let them, daddy. Don’t let the stars run down.”

“Now look what you’ve done,” whispered Jerrodine, exasperated.

“How was I to know it would frighten them?” Jerrodd whispered back.

“Ask the Microvac,” wailed Jerrodette I. “Ask him how to turn the stars on again.”

“Go ahead,” said Jerrodine. “It will quiet them down.” (Jerrodette II was beginning to cry, also.)

Jerrodd shrugged. “Now, now, honeys. I’ll ask Microvac. Don’t worry, he’ll tell us.”

He asked the Microvac, adding quickly, “Print the answer.”

Jerrodd cupped the strip of thin cellufilm and said cheerfully, “See now, the Microvac says it will take care of everything when the time comes so don’t worry.”

Jerrodine said, “And now, children, it’s time for bed. We’ll be in our new home soon.”

Jerrodd read the words on the cellufilm again before destroying it: insufficient data for a meaningful answer.

He shrugged and looked at the visiplate. X-23 was just ahead.

VJ-23X of Lameth stared into the black depths of the three-dimensional, small-scale map of the Galaxy and said, “Are we ridiculous, I wonder, in being so concerned about the matter?”

MQ-17J of Nicron shook his head. “I think not. You know the Galaxy will be filled in five years at the present rate of expansion.”

Both seemed in their early twenties, both were tall and perfectly formed.

“Still,” said VJ-23X, “I hesitate to submit a pessimistic report to the Galactic Council.”

“I wouldn’t consider any other kind of report. Stir them up a bit. We’ve got to stir them up.”

VJ-23X sighed. “Space is infinite. A hundred billion Galaxies are there for the taking. More.”

“A hundred billion is not infinite and it’s getting less infinite all the time. Consider! Twenty thousand years ago, mankind first solved the problem of utilizing stellar energy, and a few centuries later, interstellar travel became possible. It took mankind a million years to fill one small world and then only fifteen thousand years to fill the rest of the Galaxy. Now the population doubles every ten years–”

VJ-23X interrupted. “We can thank immortality for that.”

“Very well. Immortality exists and we have to take it into account. I admit it has its seamy side, this immortality. The Galactic AC has solved many problems for us, but in solving the problem of preventing old age and death, it has undone all its other solutions.”

“Yet you wouldn’t want to abandon life, I suppose.”

“Not at all,” snapped MQ-17J, softening it at once to, “Not yet. I’m by no means old enough. How old are you?”

“Two hundred twenty-three. And you?”

“I’m still under two hundred. –But to get back to my point. Population doubles every ten years. Once this Galaxy is filled, we’ll have filled another in ten years. Another ten years and we’ll have filled two more. Another decade, four more. In a hundred years, we’ll have filled a thousand Galaxies. In a thousand years, a million Galaxies. In ten thousand years, the entire known Universe. Then what?”

VJ-23X said, “As a side issue, there’s a problem of transportation. I wonder how many sunpower units it will take to move Galaxies of individuals from one Galaxy to the next.”

“A very good point. Already, mankind consumes two sunpower units per year.”

“Most of it’s wasted. After all, our own Galaxy alone pours out a thousand sunpower units a year and we only use two of those.”

“Granted, but even with a hundred per cent efficiency, we only stave off the end. Our energy requirements are going up in a geometric progression even faster than our population. We’ll run out of energy even sooner than we run out of Galaxies. A good point. A very good point.”

“We’ll just have to build new stars out of interstellar gas.”

“Or out of dissipated heat?” asked MQ-17J, sarcastically.

“There may be some way to reverse entropy. We ought to ask the Galactic AC.”

VJ-23X was not really serious, but MQ-17J pulled out his AC-contact from his pocket and placed it on the table before him.

“I’ve half a mind to,” he said. “It’s something the human race will have to face someday.”

He stared somberly at his small AC-contact. It was only two inches cubed and nothing in itself, but it was connected through hyperspace with the great Galactic AC that served all mankind. Hyperspace considered, it was an integral part of the Galactic AC.

MQ-17J paused to wonder if someday in his immortal life he would get to see the Galactic AC. It was on a little world of its own, a spider webbing of force-beams holding the matter within which surges of sub-mesons took the place of the old clumsy molecular valves. Yet despite its sub-etheric workings, the Galactic AC was known to be a full thousand feet across.

MQ-17J asked suddenly of his AC-contact, “Can entropy ever be reversed?”

VJ-23X looked startled and said at once, “Oh, say, I didn’t really mean to have you ask that,”

“Why not?”

“We both know entropy can’t be reversed. You can’t turn smoke and ash back into a tree.”

“Do you have trees on your world?” asked MQ-17J.

The sound of the Galactic AC startled them into silence. Its voice came thin and beautiful out of the small AC-contact on the desk. It said: there is insufficient data for a meaningful answer.

VJ-23X said, “See!”

The two men thereupon returned to the question of the report they were to make to the Galactic Council.

Zee Prime’s mind spanned the new Galaxy with a faint interest in the countless twists of stars that powdered it. He had never seen this one before. Would he ever see them all? So many of them, each with its load of humanity. –But a load that was almost a dead weight. More and more, the real essence of men was to be found out here, in space.

Minds, not bodies! The immortal bodies remained back on the planets, in suspension over the eons. Sometimes they roused for material activity but that was growing rarer. Few new individuals were coming into existence to join the incredibly mighty throng, but what matter? There was little room in the Universe for new individuals.

Zee Prime was roused out of his reverie upon coming across the wispy tendrils of another mind.

“I am Zee Prime,” said Zee Prime. “And you?”

“I am Dee Sub Wun. Your Galaxy?”

“We call it only the Galaxy. And you?”

“We call ours the same. All men call their Galaxy their Galaxy and nothing more. Why not?”

“True. Since all Galaxies are the same.”

“Not all Galaxies. On one particular Galaxy the race of man must have originated. That makes it different.”

Zee Prime said, “On which one?”

“I cannot say. The Universal AC would know.”

“Shall we ask him? I am suddenly curious.”

Zee Prime’s perceptions broadened until the Galaxies themselves shrank and became a new, more diffuse powdering on a much larger background. So many hundreds of billions of them, all with their immortal beings, all carrying their load of intelligences with minds that drifted freely through space. And yet one of them was unique among them all in being the original Galaxy. One of them had, in its vague and distant past, a period when it was the only Galaxy populated by man.

Zee Prime was consumed with curiosity to see this Galaxy and he called out: “Universal AC! On which Galaxy did mankind originate?”

The Universal AC heard, for on every world and throughout space, it had its receptors ready, and each receptor lead through hyperspace to some unknown point where the Universal AC kept itself aloof.

Zee Prime knew of only one man whose thoughts had penetrated within sensing distance of Universal AC, and he reported only a shining globe, two feet across, difficult to see.

“But how can that be all of Universal AC?” Zee Prime had asked.

“Most of it,” had been the answer, “is in hyperspace. In what form it is there I cannot imagine.”

Nor could anyone, for the day had long since passed, Zee Prime knew, when any man had any part of the making of a Universal AC. Each Universal AC designed and constructed its successor. Each, during its existence of a million years or more accumulated the necessary data to build a better and more intricate, more capable successor in which its own store of data and individuality would be submerged.

The Universal AC interrupted Zee Prime’s wandering thoughts, not with, words, but with guidance. Zee Prime’s mentality was guided into the dim sea of Galaxies and one in particular enlarged into stars.

A thought came, infinitely distant, but infinitely clear. “this is the original galaxy of man.”

But it was the same after all, the same as any other, and Zee Prime stifled his disappointment.

Dee Sub Wun, whose mind had accompanied the other, said suddenly, “And is one of these stars the original star of Man?” The Universal AC said, “man’s original star has gone nova. it is a white dwarf.”

“Did the men upon it die?” asked Zee Prime, startled and without thinking.

The Universal AC said, “a new world, as in such cases, was constructed for their physical bodies in time.”

“Yes, of course,” said Zee Prime, but a sense of loss overwhelmed him even so. His mind released its hold on the original Galaxy of Man, let it spring back and lose itself among the blurred pin points. He never wanted to see it again.

Dee Sub Wun said, “What is wrong?”

“The stars are dying. The original star is dead.”

“They must all die. Why not?”

“But when all energy is gone, our bodies will finally die, and you and I with them.”

“It will take billions of years.”

“I do not wish it to happen even after billions of years. Universal AC! How may stars be kept from dying?”

Dee Sub Wun said in amusement, “You’re asking how entropy might be reversed in direction.”

And the Universal AC answered: “there is as yet insufficient data for a meaningful answer.”

Zee Prime’s thoughts fled back to his own Galaxy. He gave no further thought to Dee Sub Wun, whose body might be waiting on a Galaxy a trillion light-years away, or on the star next to Zee Prime’s own. It didn’t matter.

Unhappily, Zee Prime began collecting interstellar hydrogen out of which to build a small star of his own. If the stars must someday die, at least some could yet be built.

Man considered with himself, for in a way, Man, mentally, was one. He consisted of a trillion, trillion, trillion ageless bodies, each in its place, each resting quiet and incorruptible, each cared for by perfect automatons, equally incorruptible, while the minds of all the bodies freely melted one into the other, indistinguishable.

Man said, “The Universe is dying.”

Man looked about at the dimming Galaxies. The giant stars, spendthrifts, were gone long ago, back in the dimmest of the dim far past. Almost all stars were white dwarfs, fading to the end.

New stars had been built of the dust between the stars, some by natural processes, some by Man himself, and those were going, too. White dwarfs might yet be crashed together and of the mighty forces so released, new stars built, but only one star for every thousand white dwarfs destroyed, and those would come to an end, too.

Man said, “Carefully husbanded, as directed by the Cosmic AC, the energy that is even yet left in all the Universe will last for billions of years.”

“But even so,” said Man, “eventually it will all come to an end. However it may be husbanded, however stretched out, the energy once expended is gone and cannot be restored. Entropy must increase forever to the maximum.”

Man said, “Can entropy not be reversed? Let us ask the Cosmic AC.”

The Cosmic AC surrounded them but not in space. Not a fragment of it was in space. It was in hyperspace and made of something that was neither matter nor energy. The question of its size and nature no longer had meaning in any terms that Man could comprehend.

“Cosmic AC,” said Man, “how may entropy be reversed?”

The Cosmic AC said, “there is as yet insufficient data for a meaningful answer.”

Man said, “Collect additional data.”

The Cosmic AC said, “i will do so. i have been doing so for a hundred billion years. my predecessors and i have been asked this question many times. all the data i have remains insufficient.”

“Will there come a time,” said Man, “when data will be sufficient or is the problem insoluble in all conceivable circumstances?”

The Cosmic AC said, “no problem is insoluble in all conceivable circumstances.”

Man said, “When will you have enough data to answer the question?”

The Cosmic AC said, “there is as yet insufficient data for a meaningful answer.”

“Will you keep working on it?” asked Man.

The Cosmic AC said, “i will.”

Man said, “We shall wait.”

The stars and Galaxies died and snuffed out, and space grew black after ten trillion years of running down.

One by one Man fused with AC, each physical body losing its mental identity in a manner that was somehow not a loss but a gain.

Man’s last mind paused before fusion, looking over a space that included nothing but the dregs of one last dark star and nothing besides but incredibly thin matter, agitated randomly by the tag ends of heat wearing out, asymptotically, to the absolute zero.

Man said, “AC, is this the end? Can this chaos not be reversed into the Universe once more? Can that not be done?”

AC said, “there is as yet insufficient data for a meaningful answer.”

Man’s last mind fused and only AC existed–and that in hyperspace.

Matter and energy had ended and with it space and time. Even AC existed only for the sake of the one last question that it had never answered from the time a half-drunken computer ten trillion years before had asked the question of a computer that was to AC far less than was a man to Man.

All other questions had been answered, and until this last question was answered also, AC might not release his consciousness.

All collected data had come to a final end. Nothing was left to be collected.

But all collected data had yet to be completely correlated and put together in all possible relationships.

A timeless interval was spent in doing that.

And it came to pass that AC learned how to reverse the direction of entropy.

But there was now no man to whom AC might give the answer of the last question. No matter. The answer–by demonstration–would take care of that, too.

For another timeless interval, AC thought how best to do this. Carefully, AC organized the program.

The consciousness of AC encompassed all of what had once been a Universe and brooded over what was now Chaos. Step by step, it must be done.

And AC said, “let there be light!”

And there was light–

Quizás escucharon alguna vez del extraño caso de un joven, hace ya muchos años, que recibió el impacto de una bala perdida en el centro de su corazón, y sobrevivió. Por supuesto, el caso conmovió a la sociedad en su momento; los medios, muy propensos al sensacionalismo, se dieron un festín. ¡Cómo olvidar la enorme palabra ‘milagro’ impresa en la portada de El Comercio!

Los detalles médicos del caso, que pueden ser consultados si nos dirigimos a los archivos de la prensa de ese entonces (aunque tengan que ser tomados con cuidado, pues también se dijo mucho que no correspondía con la verdad), no son, sin embargo, los que nos interesa recordar en esta ocasión. Huelga decir que, dada la perplejidad de los científicos, no tardó en llegar una comisión del Vaticano para examinar el caso. La santa investigación, no obstante, se vio truncada dada la poca cooperación por parte del joven. En realidad, digámoslo para ser más precisos, su actitud abiertamente hostil hacia la misma.

Justamente encontré, entre viejos apuntes, un recorte de la única entrevista que el joven dio a la prensa en ese entonces. Comparto el fragmento que encuentro más interesante y rico en filosofía.

Entrevistador: A pesar del entusiasmo de la gente, usted se ha mostrado reticente a colaborar con la comitiva de la Iglesia.

El joven: No puedo no decirlo. Me parece aberrante pensar en un Dios que interviene, con una suerte de poder mágico, para salvar una vida. Si es que Dios puede salvar una vida, ¿por qué salva esa y no miles de otras? Eso no es justo, y Dios no puede ser injusto. Si Dios interviene en el mundo, lo hace mediante los actos morales de las personas, no con trucos.

[…]

Entrevistador: Dicen que el más mínimo movimiento de la bala podría resultar letal… Que usted podría morir en cualquier momento…

El joven: Cualquiera puede morir en cualquier momento.

[El joven calla]

Con todo, quiero vivir. Espero vivir mucho. Ojalá Dios me lo permita.

El joven, muchos años después, ya anciano, murió de muerte natural.

La filosofía es, ante todo, una actividad racional que reflexiona. Uno de los objetos más problemáticos de la filosofía es la razón misma, a saber, el poner en tela de juicio la propia capacidad para reflexionar. El esfuerzo más importante en este sentido ha sido, sin lugar a dudas, la Crítica de la razón pura de Immanuel Kant. Es una tarea distinta, si bien relacionada, aquella que se preocupa de indagar el origen de la racionalidad en el ser humano; búsqueda que, por supuesto, debe basarse en evidencia empírica (antropológica, arqueológica, histórica, etc.).

Pero, ¿cuál es esa razón que se está buscando? ¿Qué la caracteriza? Entenderemos muy generalmente la razón práctica como aquella capacidad de fijarnos un fin, y buscar los medios para conseguirlo. Si bien, como argumentaremos más adelante, la razón en el ser humano supera infinitamente dicha capacidad, por el momento mantendremos que ese es el uso elemental de la razón en el ser humano. Esto equivale, por supuesto, a un imperativo hipotético: si quieres ‘x’ (has fijado x como un fin) entonces estás obligado a hacer ‘y’ (los medios necesarios para la consecución de dicho fin). Esta racionalidad básica se contrapone a un actuar instintivo, en el cual el fin es puesto por el instinto, a la vez que no hay una deliberación sobre los medios (dejo abierto, como una interrogante empírica, si es que otros animales además del ser humano poseen algún tipo de racionalidad, si bien muy elemental).

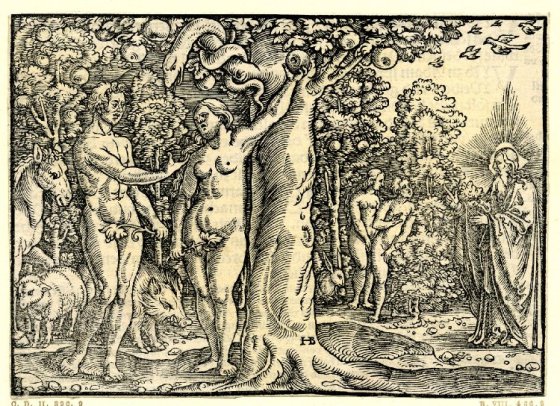

Un intento de definir exactamente cómo aparece esta capacidad en el ser humano fue llevado a cabo también por Kant en su artículo «Probable inicio de la historia humana» (1786), donde señala que la razón despierta en el ser humano gradualmente a lo largo de un extenso periodo de tiempo. De esta forma, son cuatro los momentos que identifica Kant, y que corresponden a cuatro características fundamentales de la razón humana. El objetivo de esta entrada será examinar estos cuatro momentos, de modo que ilustremos qué capacidades concretas subyacen la actividad humana en tanto la actividad de un ser racional (en el objetivo está implícito que el género Homo, de más de dos millones de antigüedad, no siempre ha contado con la racionalidad como característica ; esto se condice, por cierto, con lo que se sabe actualmente del origen de nuestra especie).

La razón empieza a despertar en el ser humano cuando deja de buscar alimentos únicamente guiado por el sentido del olfato (estrechamente ligado con el del gusto), a saber, instintivamente, y empieza en vez «mediante la comparación de lo ya saboreado con aquello que otro sentido no tan ligado al instinto —cual es el de la vista— le presentaba como similar a lo ya degustado, [a tratar] de ampliar su conocimiento sobre los medios de nutrición más allá de los límites del instinto» (Kant 2006: 60; Ak 8:110).

Kant identifica este despertar con el mito bíblico de la caída, pues el ser humano ensaya probar un fruto que le es prohibido por la naturaleza, es decir, por el mero instinto, y esto resulta en su muerte (por ejemplo, probar un fruto venenoso porque era similar a uno no venenoso). Semejante daño, no obstante, resultaba insignificante en la medida que el ser humano descubría en sí mismo la «capacidad para elegir por sí mismo su propia manera de vivir y no estar sujeto a una sola forma de vida como el resto de los animales» (Kant 2006: 62; Ak 8:111).

El segundo momento se refiere ya no al instinto de nutrición, sino al instinto sexual:

La razón, una vez que despierta, no tardó en probar también su influjo a este instinto. Pronto descubrió el hombre que la excitación sexual —que en los animales depende únicamente de un estímulo fugaz y por lo general periódico— era susceptible en él de ser prolongada e incluso acrecentada gracias a la imaginación, que ciertamente desempeña su cometido con mayor moderación, pero asimismo con mayor duración y regularidad, cuanto más sustraído a los sentidos se halle el objeto, evitándose así el tedio que conlleva la satisfacción de un mero deseo animal. (Kant 2006: 62; Ak 8:111-112)

El cubrirse los genitales «muestra ya la conciencia de un dominio de la razón sobre los impulsos», supone «una inclinación a infundir en los otros un respeto hacia nosotros» y constituye el «verdadero fundamento de toda auténtica sociabilidad», a la vez que «la primera señal para la formación del hombre como criatura moral», a saber, la decencia (Kant 2006: 62-63; Ak 8:112).

El tercer paso «fue la reflexiva expectativa de futuro«, que le permitió al ser humano proyectarse más allá del momento actual, y concebir, en pareja y con sus hijos (o futuros hijos), aquel momento que «también afecta inevitablemente a todos los animales, pero no les preocupa en absoluto: la muerte»[1] (Kant 2006: 63-64; Ak 8:113).

Hasta el momento tenemos a los seres humanos preocupados en obtener y mantener todo conocimiento que les permita alimentarse y sobrevivir, a la vez que se relacionan mutuamente más allá de cualquier inmediatez, de modo que se puede hablar ya de la existencia de normas que delimitan que está y no está permitido en lo que respecta a la satisfacción de los deseos sexuales. Además, todo esto se hace ya con una perspectiva a futuro, con un entendimiento del fin inevitable de la existencia (entierro de los muertos). Esto nos lleva al cuarto y último paso, que, se podría argumentar, todavía no se ha dado del todo:

El cuarto y último paso dado por la razón eleva al hombre muy por encima de la sociedad con los animales, al comprender éste (si bien de un modo bastante confuso) que él constituye en realidad el fin de la Naturaleza y nada de lo que vive sobre la tierra podría representar una competencia en tal sentido. (Kant 2006: 64; Ak 8:113)

Esto corresponde a tomar conciencia de que los objetos del mundo pueden ser usados como medios, y, por lo tanto, el ser humano mismo debe representarse como algo que no puede ser usado sólo como medio, sino que debe ser tratado como un fin en sí mismo, lo que le confiere el valor más elevado concebible, a su vez, fundamento de toda la moralidad.

Así, la razón, en su elemento más básico de un imperativo hipotético, conlleva necesariamente la conciencia de un imperativo categórico, es decir, la obligación de tratarse a sí mismo a la vez que a sus congéneres con el respeto que exige esta condición. Resulta evidente la simpatía de Kant hacia el mito bíblico de la caída, que lejos de ser tomado literalmente, refleja cómo de ciertas capacidades elementales, en tanto suponen una elección, al mismo tiempo implican mucho más: la existencia, por primera vez, de la facultad de reconocer el bien y el mal.

La razón, concluimos, no puede pensarse sin este elemento moral, que le es propio.

[1] El ser para la muerte es una característica fundamental del ser humano en tanto ser racional.

Bibliografía:

KANT, Immanuel

Ideas para una historia universal en clave cosmopolita y otros escritos sobre Filosofía de la Historia. Traducción de Concha Roldán Panadero y Roberto Rodríguez Aramayo. Tercera edición. Madrid: Editorial Tecnos, 2006.

Todo fluye.

Según el pensamiento de Fiódor Dostoievski, de la mano de dos de sus personajes, primero del príncipe Myshkin (El idiota, primeras dos entradas) y luego del stárets Zosima (Los hermanos Karamázov, las dos restantes). Cada entrada corresponde a un fragmento de la obra religiosa del escritor ruso (el pensamiento doctrinal presente en sus novelas). Se recomienda leer las entradas en orden. Van.

Una definición negativa de lo que es la religión en un discurso parabólico: Las cuatro historias del príncipe Myshkin: una “refutación” del ateísmo (o sobre lo que es propio de la religión).

Sobre la interioridad del ser humano, la insondabilidad que le es propia, y lo que significa en nosotros: Ideas dobles (o sobre lo insondable en las propias motivaciones).

La mentira interior: Sobre la mentira interior.

El mal radical o el pecado original, o, en realidad, sobre el modo compartido de la conciencia moral: La vida monacal y el mal radical de nuestros corazones.

Y para cerrar, una concepción mística de divinidad según Erich Fromm: ¿Qué es Dios? Una concepción existencial, mística y práctica.

Post de domingo.

Demos una respuesta, en realidad, bastante sencilla: cualquier conocimiento que pretenda objetividad debe validarse intersubjetivamente.

En esta línea, Immanuel Kant señala que «contrastar el propio juicio apelando al entendimiento de los demás» constituye la «piedra de toque (criterium veritatis externum)«, el medio del cual no podemos prescindir para asegurarnos de la verdad de nuestros propios juicios (2004: 27).

Ni siquiera una disciplina como la Matemática estaría exenta de dicho criterio, «pues si no hubiese ido por delante la universal concordancia percibida entre los juicios del matemático con el juicio de todos los demás que se han dedicado con talento y solicitud a esta disciplina, no se habría sustraído ésta a la inquietud de incurrir en algún punto de error» (Kant 2004: 27).

De esta forma, el conocimiento objetivo nunca es absoluto, puesto que, por la humildad de nuestro propio entendimiento, tenemos que aceptar que lo que sabemos podría verse refutado, o explicado de forma más precisa, por otros, inclusive en el futuro. Es así que la ciencia avanza.

La persona que pretende no necesitar de esta validación es denominado por Kant como egoísta lógico.

Esto, por supuesto, refiere a una concepción de la razón humana intrínsecamente intersubjetiva, cuya misma existencia depende del diálogo libre entre ciudadanos del mundo.

Para un par de entradas relacionadas, ver: ¿Qué es la razón? (o sobre propiedades monádicas y relacionales) e Intersubjetividad.

Bibliografía:

KANT, Immanuel

Antropología en sentido pragmático. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2004.